The coaching profession has moved from the margins to the mainstream. Recent global studies show that the number of professional...

Over the past two centuries, women’s roles in society and leadership have undergone a remarkable transformation. From the early suffrage movements to the election of women to the highest offices and the boardrooms of global corporations, women have continually challenged barriers and redefined what leadership looks like. Yet progress has not been linear; gains have been won through persistence, collective action, and the support of allies. At the start of the 21st century, women hold more leadership positions than ever before, but disparities remain. This comprehensive guide charts the evolution of women’s leadership, highlights why it matters for businesses and societies, examines ongoing challenges, and provides actionable strategies for creating an equitable future.

Women’s leadership did not emerge overnight; it was forged in the crucible of social movements, war efforts, and cultural shifts. Understanding the historical context helps us appreciate the progress made and the work that remains.

While women have made significant strides, leadership remains far from gender-parity. Recent statistics reveal both progress and ongoing gaps:

Metric | Value/Statistic |

|---|---|

Women in senior leadership roles globally | Approximately 31% of senior leadership roles worldwide are held by women, a modest increase from 29% in 2022. |

Fortune 500 female CEOs (2023) | 53 female CEOs lead Fortune 500 companies, representing 10.6% of the total and up from zero in 1995. |

Representation on corporate boards | Women occupy roughly 29% of board seats in top companies worldwide; in the UK FTSE 350, women hold 42% of board positions but only 10 CEO roles. |

Women of colour in C-suite roles | Only about 7% of C-suite positions are held by women of colour, highlighting intersectional gaps. |

DEI impact on representation | Organizations with robust diversity, equity, and inclusion programs see an average of 35% women in leadership compared with 25% in those without such initiatives. |

These figures show that while there has been steady progress, women—especially women of colour—remain underrepresented in top leadership positions. The slow pace of change underscores the need for sustained efforts to dismantle systemic barriers and promote gender equity.

The growing presence of women in leadership is not merely a matter of fairness; it has measurable benefits for organizations and societies. Research consistently shows that companies with greater gender diversity on their leadership teams outperform those with homogenous leadership. Diverse perspectives foster creativity, reduce groupthink, and lead to better decision-making. Women leaders often bring collaborative, empathetic, and inclusive styles that resonate with today’s workforce, driving engagement and retention.

At a macro level, empowering women leaders contributes to economic growth. The World Economic Forum estimates that closing the gender gap in labour force participation could increase global GDP by trillions of dollars. Women leaders also serve as role models for younger generations, inspiring girls and young women to pursue leadership paths. Additionally, women in power often champion policies related to education, health, and social welfare, leading to broader social benefits.

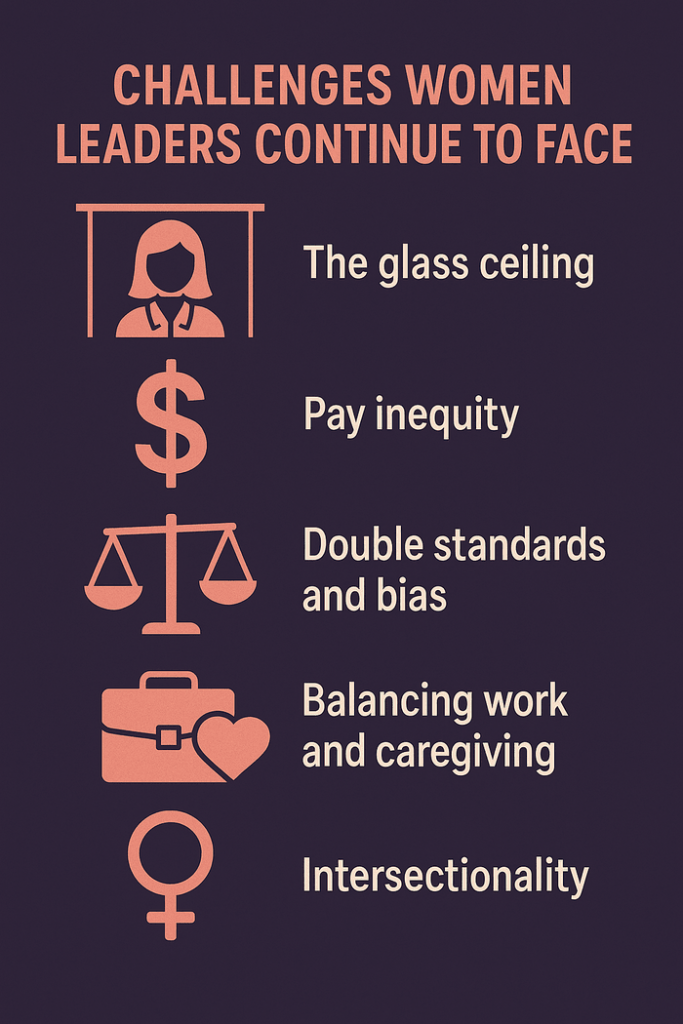

Despite the clear advantages of gender diversity, women leaders encounter persistent obstacles. Among the most pressing challenges are:

Addressing these challenges requires collective action from organizations, policymakers, and individuals. Here are evidence-based strategies to advance women’s leadership:

Real-world stories demonstrate the power of women’s leadership. Consider the rise of Mary Barra, who began her career at General Motors as a co-op student and, after decades of dedication and innovation, became the company’s first female CEO. Under her leadership, GM has invested heavily in electric vehicles and pursued ambitious sustainability goals.

In India, Falguni Nayar left a successful investment banking career to found Nykaa, a beauty e-commerce platform. Her entrepreneurial vision and understanding of consumers propelled Nykaa to a billion-dollar valuation, making her one of the wealthiest self-made women in the world.

On the global stage, New Zealand’s former Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern demonstrated empathetic crisis leadership, leading her country through natural disasters and a pandemic while prioritizing kindness and unity. Her approach showed that strength and compassion are not mutually exclusive. These examples underscore that when women lead, they bring unique perspectives and drive transformative outcomes.

Looking ahead, several trends will shape the next chapter of women’s leadership. The rise of remote and hybrid work could open opportunities for women who require flexibility, though it also risks reinforcing biases if not managed inclusively. Millennials and Generation Z—more attuned to social justice and equality—are ascending into leadership roles, likely accelerating diversity efforts. Technologies like artificial intelligence and automation will reshape the workforce, making continuous upskilling essential. Women leaders can influence how these technologies are developed and deployed, ensuring they serve diverse needs and avoid perpetuating inequities.

Moreover, the focus on environmental, social, and governance (ESG) criteria provides a platform for women leaders to champion sustainability and ethical business practices. As stakeholders increasingly demand responsible leadership, organizations led by diverse teams will be better positioned to respond.

The evolution of women’s leadership is often told through the stories of well-known figures, yet countless pioneers worked in the shadows, laying the foundation for future leaders. In the 18th and 19th centuries, Madam C.J. Walker built a hair-care empire as one of America’s first self-made female millionaires. Her success not only demonstrated entrepreneurial talent but also created jobs and opportunities for thousands of Black women during a period when racial and gender discrimination were rampant.

In the realm of science, Marie Curie became the first woman to win a Nobel Prize and remains the only person to receive Nobel Prizes in two scientific fields. Her groundbreaking research on radioactivity expanded the boundaries of physics and chemistry and shattered stereotypes about women’s intellectual capabilities. Similarly, pioneering computer scientist Ada Lovelace wrote the first algorithm intended for a machine, envisioning the potential of computing long before it became reality.

Women’s leadership also flourished in activism and social reform. Ida B. Wells bravely confronted lynching in the United States, using investigative journalism to expose atrocities and mobilize public opinion. Emmeline Pankhurst led the British suffragette movement, enduring imprisonment and force-feeding in her fight for voting rights. Sarojini Naidu, known as the Nightingale of India, combined poetry with political activism to champion women’s rights and India’s independence. These pioneers—and many unnamed others—exemplify resilience and courage in the face of systemic barriers.

During the mid-20th century, women broke through in corporate and political spheres. Katherine Johnson, one of NASA’s “hidden figures,” calculated trajectories that enabled the success of U.S. space missions. Her story, like that of other African American women mathematicians and engineers, remained largely unrecognized until decades later. On the political front, Sirimavo Bandaranaike of Sri Lanka became the world’s first female prime minister in 1960, paving the way for female heads of state worldwide. Golda Meir served as Israel’s prime minister in the 1970s, navigating complex geopolitical challenges.

By highlighting these trailblazers, we recognize that women’s leadership has always been present, even when society failed to acknowledge it. Their stories remind us that progress hinges not only on visible breakthroughs but also on the persistence of those who push boundaries quietly, leaving a legacy for future generations.

Women’s leadership cannot be understood without examining the intersecting identities that shape experiences. Coined by scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw, intersectionality describes how gender intersects with race, class, sexuality, disability, and other identities to produce unique forms of oppression and privilege. Women of colour, LGBTQ+ women, and women with disabilities often face compounded discrimination that is invisible in mainstream narratives.

For instance, Black women leaders navigate both sexism and racism. They contend with stereotypes that cast them as either overly aggressive or overly nurturing. Despite these obstacles, Black women have made significant strides. Sheryl Sandberg noted that in the United States, Black women are the most educated demographic group, yet they are significantly underrepresented in leadership roles. Figures like Ursula Burns, who became the first Black woman CEO of a Fortune 500 company (Xerox), demonstrate that intersectional representation is possible, but she remains an exception.

Indigenous women leaders face unique challenges tied to cultural preservation and land rights. Evo Morales’s ousting in Bolivia in 2019 led to the appointment of Jeanine Áñez, but her government marginalized Indigenous voices. In contrast, figures like Sahle-Work Zewde, Ethiopia’s first female president, emphasize inclusive governance, highlighting how intersectional leadership can uplift marginalized communities.

LGBTQ+ women leaders contribute critical perspectives on diversity and inclusion. Leaders such as Martine Rothblatt, a transgender woman who founded Sirius Satellite Radio and biotech company United Therapeutics, break barriers and expand society’s understanding of gender and identity. Women with disabilities, like activist and Harvard Law graduate Haben Girma, advocate for accessibility and demonstrate that leadership transcends physical limitations.

Addressing intersectionality requires dismantling multiple layers of bias. Organizations must go beyond gender representation quotas and examine how race, sexuality, ability, and socioeconomic status intersect. Doing so ensures that leadership pipelines include women from diverse backgrounds and that policies address specific barriers faced by different groups. Intersectional leadership enriches decision-making, fosters empathy, and reflects the complexity of the communities organizations serve.

Progress in women’s leadership has been accelerated by policies and legislation that dismantle legal barriers. In the United States, the 19th Amendment (1920) granted women the right to vote, while Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibited employment discrimination based on sex. The Equal Pay Act of 1963 aimed to eliminate wage disparities. Subsequent legislation, including the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) and the Pregnancy Discrimination Act, protected women’s rights to maternity leave and freedom from pregnancy-based discrimination.

Internationally, instruments like the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), adopted by the United Nations in 1979, call on countries to ensure women’s equal participation in public life. Many nations have implemented gender quotas for political representation—Rwanda’s constitution reserves 30% of parliamentary seats for women, resulting in one of the highest percentages of female legislators in the world. In the corporate arena, countries like Norway mandated that public company boards have at least 40% female representation, spurring similar initiatives across Europe.

These legislative milestones demonstrate the power of policy in accelerating change. However, enforcement and cultural shifts remain critical. Laws can open doors, but organizations and societies must embrace the spirit of equality for policies to be effective. Continuing to advocate for robust enforcement and expanding protections for marginalized women will help close remaining gaps.

Advancing women’s leadership is not solely women’s work; men play a crucial role as allies and partners. Male leaders occupy many positions of power and can leverage their influence to champion gender equity. Allies can do this by sponsoring talented women, challenging biased comments or behaviours, and ensuring that women’s ideas are heard and credited. Studies show that when men actively participate in diversity initiatives, progress happens faster and is sustained longer.

Organizations can foster male allyship through training programs that explore topics like unconscious bias and privilege. Employee resource groups focused on gender equality can include men as members, encouraging them to listen to women’s experiences and co-create solutions. Companies like HeForShe—an initiative launched by UN Women—mobilize men worldwide to support gender equality. At PwC, the HeforShe campaign has led male executives to advocate for equal pay and mentorship opportunities for women.

It is also important to engage men in conversations about work-life integration. When men take parental leave and participate in caregiving, they normalize shared responsibilities and reduce stigma for women. Policies that make parental leave gender-neutral encourage men to utilize benefits, fostering a culture where caregiving is not seen as a solely female role. Men’s engagement is essential not only for fairness but also because gender equality benefits everyone—organizations with diverse leadership are more innovative and employees with supportive policies enjoy better well-being.

Although leadership styles vary widely among individuals, research has identified trends in how women leaders tend to lead. Many studies have found that women are more likely to adopt a transformational leadership style—motivating and empowering followers through vision, inspiration, and personal attention. Transformational leaders focus on developing others, encouraging innovation, and creating inclusive cultures. Women are also more likely to use collaborative and participative approaches, seeking input from their teams and building consensus.

These strengths are not innate to women but arise in part from socialization and experiences. Because women have historically been excluded from formal power, they often learn to lead by influence rather than authority. They develop skills in negotiation, empathy, and relationship-building that become assets in modern, knowledge-based economies. Studies cited by management scholars indicate that organizations with more women in leadership positions exhibit better collaboration, problem-solving, and ethical conduct. It is important, however, not to pigeonhole women into particular leadership styles; individuals of any gender can exhibit a range of approaches.

Another area where women leaders excel is emotional intelligence (EI). EI encompasses self-awareness, self-regulation, motivation, empathy, and social skills. High EI enables leaders to navigate complex interpersonal dynamics, manage stress, and inspire trust. Women, on average, score higher than men on measures of empathy and social skills, which can enhance team cohesion and conflict resolution. Encouraging all leaders to develop EI fosters healthier and more productive workplaces.

To ensure that efforts to advance women’s leadership yield results, organizations must track progress and hold themselves accountable. Metrics can include:

Publishing annual diversity reports is a best practice that promotes transparency and encourages accountability. External assessments, such as gender equality indices or certifications, provide benchmarks and motivate improvement. Setting specific, time-bound targets for gender diversity and linking executive compensation to DEI goals can further drive progress.

Ultimately, measuring progress is not about achieving arbitrary quotas but about creating systems that enable all talented individuals to thrive. Continuous monitoring ensures that initiatives remain effective and that complacency does not undo hard-won gains.

While trends toward gender equality in leadership are global, progress varies widely by region. In Nordic countries such as Iceland, Norway, and Finland, strong social policies—universal childcare, generous parental leave, and quotas for corporate boards—have propelled women into leadership roles. These nations consistently rank high on gender equality indices, demonstrating the impact of supportive policies. In contrast, regions with entrenched patriarchal norms or limited legal protections see slower progress.

In parts of Asia and the Middle East, cultural expectations and legal constraints continue to restrict women’s leadership opportunities. Nevertheless, notable exceptions exist. For example, Saudi Arabia has recently opened avenues for women in business and government, appointing women to senior ministerial posts and granting them new rights in entrepreneurship. In Africa, Rwanda’s parliament boasts over 60% female representation, a result of post-genocide constitutional reforms that prioritized gender inclusion. Ethiopia and Namibia have also achieved gender parity in cabinets.

Understanding regional differences helps organizations tailor strategies. Multinational corporations must navigate varied cultural norms and legal frameworks, balancing respect for local customs with commitments to equality. Local women leaders often best understand how to advocate for change within their cultural context. Supporting grassroots initiatives, collaborating with local NGOs, and learning from successful regional models can accelerate progress. Global conversations about women’s leadership should therefore amplify voices from all regions, recognizing that solutions are not one-size-fits-all but must respond to diverse challenges and opportunities.

Women have travelled a long road from being denied basic rights to leading nations and corporations. Each generation has built on the struggles and successes of those before it, pushing boundaries and redefining possibilities. While progress is undeniable, the journey toward gender-equitable leadership is far from over. Persistent gaps in representation, pay, and inclusion remind us that complacency is not an option.

As organizations and societies, we must not only celebrate women’s achievements but also commit to removing the systemic barriers that hinder progress. Investing in women’s leadership is an investment in our collective future—it spurs innovation, strengthens economies, and fosters more just and compassionate communities.

Whether you are a leader, a policymaker, or an individual ally, you can contribute to this evolution. Advocate for fair policies, mentor and sponsor rising women leaders, challenge bias when you see it, and champion diversity in all its forms. Together, we can accelerate the evolution of women’s leadership and create a world where leadership truly reflects the richness of human talent.

For statistics and further reading on women in leadership, consider visiting an external resource: Women in Leadership Statistics to explore current data and trends.

As of 2024, women hold approximately 31% of senior leadership roles worldwide, a slight increase from 29% in 2022. Progress is stronger in board seats (around 29-30%) but slower in C-suite positions.

In 2025, 55 women serve as CEOs of Fortune 500 companies, representing 11% of the total—a record high and up from 52 in 2024, though women remain underrepresented.

Women's leadership drives innovation, better decision-making, and economic growth through diverse perspectives that reduce groupthink and enhance collaboration. It also boosts company performance and advances social policies on health, education, and equity.

Women face the glass ceiling, pay inequity, harsher scrutiny, work-life balance challenges due to caregiving, and intersectional biases. Women of color, holding only about 7% of C-suite roles, face compounded discrimination.

Implement DEI programs with clear goals, mentorship and sponsorship, flexible work policies, leadership training for women, bias awareness campaigns, and equitable opportunities to foster inclusive cultures and accelerate gender parity.

The coaching profession has moved from the margins to the mainstream. Recent global studies show that the number of professional...

India’s economy has transformed dramatically over the last decade, and the demand for top business coach India services has grown...

When searching for a certified life coach program price, it’s natural to start by comparing tuition fees. Aspiring coaches want...

Neuro-Linguistic Programming (NLP) is experiencing a resurgence in India. Social media, workshops and high-energy seminars promise instant breakthroughs by rewiring...

Many professionals pursue the title of Certified Organizational Development Coach with the expectation that a credential alone will open corporate...

Some providers offer to fast-track you to PCC status through purely online modules for a fraction of the cost of...

Executive coaching has evolved from a niche service for struggling leaders into a strategic investment for organisations aiming to build...

When prospective coaches research training options, cost is often the first number they look for. A quick internet search produces...

Deciding to invest in life coach training programmes can be a transformative milestone in your personal and professional journey. In...